As part of our continuing endeavor to honor and remember the amazing men and women who sacrificed their time, talents, and in many cases their very lives to protect the cause of freedom the team here at Freedom Vehicles has decided to provide a weekly spotlight of veterans. These “Sunday Spotlights” will pay tribute to the many ordinary citizens who when finding themselves called to take part in extraordinary events heeded that call no matter the cost. They will also provide a brief synopsis of specific battles or conflicts related in the spotlight. As always, we welcome comments, suggestions, and stories from our readers’ families.

2017 marks the 100th anniversary of the United States entrance into WWI, and so we felt it only fitting to begin this endeavor with a tribute to a veteran of

“The War to End All Wars”.

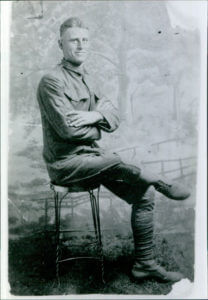

On July 16, 1892 in the quaint town of Mize, Mississippi, my great grandfather, William Grover Yelverton, was born. Life was simple for that farm boy with sky blue eyes and a smile that produced two dimples. He was raised in a large family that grew up on love, hard work, and good ole southern food and values. As his granddaughter, I have the honor of affectionately calling him “Daddy Grover”. In the summer of 1917, one hundred years ago this month, Daddy Grover was drafted into WWI. For a young man whom had never been anywhere but home, I can only imagine what he felt at this call. I have a photo of him that was taken at the end of his basic training that to this day sits framed on my piano. The young man I see in that photo was handsome, healthy, confident and courageous. I believe he was excited for unseen adventures as he donned a crisp new uniform, haircut and skills. Since his media exposure consisted solely of the small local newspaper, his expectations of the outside world were most likely created in the chambers of his own imagination. Although I am certain there were fears of the unknown, I believe his bravery stood out front and center. I am so thankful we have the photo of that unseasoned boy because the man that returned home at the end of the war was a different person. Upon receiving his draft notice, he was assigned to the 18th (this later became the 39th) Infantry Division, 114th Engineers and sent to Camp Beauregard, LA for training. Sickness and disease ran rampant at Camp Beauregard and during the end of 1917 and early 1918, the camp was plagued by outbreaks of measles, meningitis, and Spanish Flu. This led to lobar pneumonia in many patients; overcrowding the already taxed hospital facilities. The soldiers were anxious to get to France because of bug infestations and poor conditions. The 39th infantry shipped out August 6th, 1918 with the last unit arriving in France on September 12th. The Meuse-Argonne Offensive (the greatest American involvement of the war) began September 26, 1918 and infantry divisions were quickly depleted. Manpower situations became so desperate that all available troops, including those just arriving in France and those slated as training or depot divisions; such as the 39th; were deployed to the front lines. In November 1918, the 39th were moved to Aignan and several of its components, including the 114th Engineers were transferred to combat duty. As part of this action, my great grandpa helped build bridges and laid railroad tracks for the 1st Army Corps during the Meuse-Argonne drive. It was during this time that he suffered the debilitating effects of mustard gas at the hands of the German army. As the war drew to an end, the 114th Engineers returned home to Newport News, VA April 12th, 1919 aboard the battleship USS Nebraska. The mustard gas my great grandfather was exposed to caused permanent damage to his lungs that affected him the rest of his life. When he came home from the war, industry was changing the world he left behind. Most young people were honing skills and technology that had never existed or been available to rural farm boys. It was an exciting season in the history of America. For a time, my great grandpa worked on the railroad but his difficulty breathing combined with the physical requirements of the job meant he often needed to stop a moment to catch his breath. His employers were not sympathetic to his plight and he was ridiculed for not working fast enough and sitting down on the job would not be tolerated. One discouraging day, he came home from work and told my great grandmother that he could no longer keep up and had to quit his job. This was troubling to them both at the dawn of their young family. The only option Daddy Grover felt he had was to become a farmer where he could work at his own pace. Farming filled their bellies but not their pocket books and he and my great grandmother struggled most of their lives trying to make ends meet for them and their nine children. The trauma of war created many other struggles for this good man. Loud or sudden noises would make him jumpy and give him flashbacks. My grandmother (his daughter), remembered a time she was in the field with her dad. The approaching drone of a small twin engine plane in the distance caused him to jump and run toward the trees for cover. That was twenty years or more after he had been in the war and yet, the trauma still lingered. At that time, the term “shell-shocked” was newly coined and highly misunderstood. Originally thought to have been brain damage caused by exploding shells, soldiers and veterans who experienced this were considered emotionally weak, lazy and cowardly. They were often reprimanded, labeled, court martialed and some were even executed for this condition. Once, while confiding in a counselor at the VA hospital about some of his symptoms, Daddy Grover was denied sympathy but told he was probably “just schizophrenic”. Dejected, he vowed to never return to the VA. With such limited resources, many veterans turned to alcohol to self-medicate but thankfully, somehow, my great grandpa escaped that trap. Instead, he found therapy in nature- gardening and taking long walks in the woods. I wonder what occupied his thoughts on those moments of solitude. I imagine he battled feelings of inadequacy, fear, and anxiety but I also hope that he felt God’s love and grace as he navigated through those storms of life. He found companionship in his beloved mule, Henry, but ultimately, his oldest son, “Brother”, became his best friend and confidant. Daddy Grover was very protective of his children and made it his personal responsibility to keep others out of harm’s way. It is my personal belief that his strong nature to protect and defend was a blessing to many during his war days. For the man whose future at one point seemed full of possibility and adventure, those ambitions were ultimately shelved for a simpler life. He gave so much to our freedoms and the price he paid was loss of respect and health. And though he may have been disheartened by his limitations, the time he spent sharing simple joys with his children and grandchildren- like how to pull up a row of peanuts in one fell swoop or how to cut a watermelon like a champ are the moments I wish I could have witnessed with my own eyes. After a lifetime of wheezing, pain, and coughing, William Grover Yelverton died in 1965 at the age of 73 from lung cancer due to damage sustained from mustard gas. I never got to know him in this life, but earthly bounds can’t break the connection I feel to him. Today marks 125 years since William Grover Yelverton was born and I want to pay homage to the man who gave so much and received so little. Although this tribute is long overdue, his sacrifice has never expired. The opportunities he dreamed of and fought for may not have been enjoyed in his own life, but were gifted to me instead. So in honor of his birthday, I would like to express my gratitude to my great grandfather and the many others who personally paid for our freedoms. by Melissa Knapp